Pathway to Progress: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Scripto Strike

History has long been portrayed as a series of “great men” taking great action to shape the world we live in. In recent decades, however, social historians have focused more on looking at history “from the bottom up,” studying the vital role that working people played in our heritage. Working people built, and continue to build, the United States. In our new series, Pathway to Progress, we’ll take a look at various people, places and events where working people played a key role in the progress our country has made, including those who are making history right now. Today’s topic is the 1964-65 Scripto Strike in Atlanta and Martin Luther King Jr.

When talking about Martin Luther King Jr., it’s important to note that he was an activist for economic and labor rights, not just civil rights. King’s death came while he was in Memphis, Tennessee, supporting sanitation workers and AFSCME members. His support for unions and collective bargaining rights was a key part of his agenda and that support went public in Atlanta during the Scripto Strike that began in 1964.

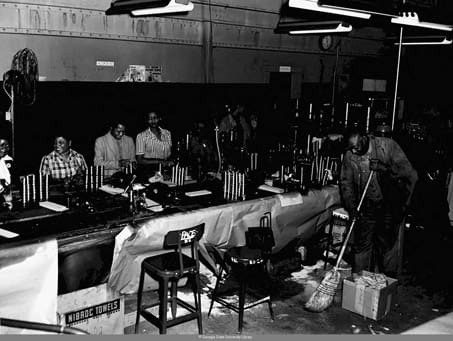

In the 1960s, Scripto was a leading pen and pencil manufacturer. The company had a plant in Atlanta since 1931 and were not only one of the largest employers in the city, but the company took pride in being the preferred employer for Black women, particularly in the area of town closest to the plant. Scripto President James V. Carmichael was surprised in 1962, when the International Chemical Workers Union started organizing at the plant. Carmichael believed that he and Scripto should be exempt from race-based complaints, as he took pride as a progressive on the topic, providing better policies for Black workers than the rest of the White Atlanta business community. Carmichael was too far removed from Black workers, though, to understand their needs and hopes and he underestimated their desire for a voice and some power in their economic lives.

The Chemical Workers Union sent the Rev. James Hampton, a Black organizer who was also a Baptist minister, to work with the Scripto employees. He tied the union organizing he was doing to the work that Martin Luther King Jr. was doing with civil rights. Hampton reached out to Black Baptist ministers in the area, recognizing that many of the Scripto workers were parishioners at their churches. King and most of the other Black ministers supported the organizing drive, speaking on behalf of the workers from the pulpit.

Support from the churches significantly boosted the union drive such that by August 1963, the Chemical Workers had collected enough union cards to petition the National Labor Relations Board for a union election. Scripto was confident it would win the election, so it agreed to a quick turnaround and an election date was set for late September. Management quickly made some minor changes, such as organizing an employee committee and removing segregation signs from bathrooms and drinking fountains. Events that spring and summer across the country had the Scripto workers primed for action, however, as they saw civil rights demonstrations having an effect in the South and beyond.

Nearly 95% of the 1,005 eligible voters participated in the election on Sept. 27, 1963. The union side won, 519-428. Within a week, Scripto began to stall. It filed objections with the NLRB that the appeals to civil rights and race by organizers tainted the election and it should be invalidated. The NLRB repeatedly rejected Scripto’s objections until June 9, 1964, when the NLRB in Washington, D.C., certified the Chemical Workers as the union representative for the plant’s workers. Scripto stalled on contract negotiations as long as it could and organizers realized that a contract wouldn’t come without a strike.

The day before Thanksgiving 1964, a mass of workers walked into the union office and demanded a strike. They worked tirelessly over the holiday and the picket lines were in place when the plant opened the day after Thanksgiving. The workers were unified. Even those who voted against the union largely supported the strike. The “no” vote for many was out of fear of management retaliation more than opposition to union goals and they rejected initial offers from Scripto as discriminatory. Approximately 85% of the plant’s workforce were Black and most were classified as “unskilled workers.” They were offered half the pay raise that the “skilled workers,” who were mostly White, were to be given. The Chemical Workers membership wouldn’t accept that deal.

The ministers of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference became involved in the strike because so many of their parishioners were Scripto employees. Led by SCLC director of affiliates C.T. Vivian, they brought their members’ concerns about wages and working conditions at Scripto to King’s attention. King and the other SCLC ministers, while philosophically sympathetic to the labor movement, they were Southerners and thus unions were outside their life experience. Once the cause of the Scripto workers was put on their radar, though, the potential for alliance was obvious to most, including King.

Vivian, King and others launched a nationwide boycott of Scripto products in support of the strike. As the strike moved on, management refused further pay increases and refused to withhold union dues from employee paychecks, despite giving some on salary increases. By Christmas, the union’s resources were virtually exhausted and the company’s leadership began to worry about two federal contracts they had and whether the company would be in compliance with an executive order on equal opportunity issued by President John F. Kennedy.

By that point, Carmichael had been replaced by Carl Singer as president and CEO of Scripto. Singer had just come off of a successful tenure as president of the Sealy Mattress Company in Chicago. Singer and King began a series of secret meetings and they worked out a broad framework to end the strike. The company negotiated in good faith and the strike came to an end on January 9, 1965, after six weeks. They soon agreed to a new contract and the Chemical Workers won most of what they asked for. Over time, the company moved towards a more favorable bargaining atmosphere and began to work more directly with the union by the 1970s until the plant shut down in 1977.

The unity established between the labor movement and the civil rights movement during the Scripto strike endured. The SCLC was heavily involved in the labor movement from that point forward and when asked if the Scripto strike would be King’s only involvement in labor conflicts, he simply said, “There will be many more to follow.” The Scripto strike taught King and others that solidarity and unity are key on the pathway to progress.

Source: Atlanta History Center

Kenneth Quinnell

Tue, 01/19/2021 – 10:05